Covid-19 And The Lockdown-A Discussion On Who Has Been Hit The Most

Covid-19 and the lockdown-a discussiion o who has been hit the most. In trying to limit the spread of COVID-19, policymakers globally have the difficult task of balancing the positive health effects of lockdown against their economic costs, particularly the burdens lockdowns impose on low-income and food-insecure households. In the case of South Africa, the lockdown policies are relatively stringent, and the economic impacts large.

The lockdown has two components. First, people have restricted their movement outside their homes and engaged in physical distancing. The result has been a dramatic decline in demand for services. These range across establishments like restaurants, theatres, sporting events and hotels.

Second, government has shuttered operations of non-essential industries to prevent spread of the disease at the workplace. Some industries closed voluntarily to stop the spread of the disease in their factories. In addition, the economic uncertainty associated with the lockdowns globally has led to declines in investment and international trade that are causing further economic contraction.

Where it has hurt most

The largest initial shocks were in mining, service sectors and non-essential industries directly affected by the lockdowns. Indirect linkages in the economy spread the impact across all industries. For example, because many business operations, including some in manufacturing, operate at low levels or not at all, demand for electricity has declined. This, in turn, has reduced the demand for coal.

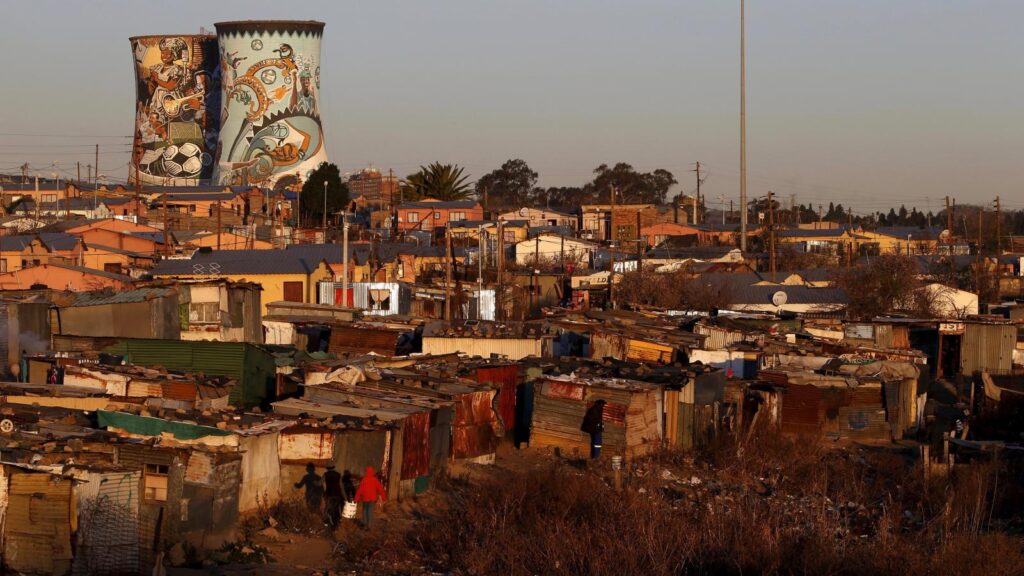

Employment also fell dramatically. Low-skilled, less-educated workers have been hit the hardest. The net effect is that the shocks are most severe on poorer, more vulnerable households. In South Africa government transfers have helped to substantially support total income of households in the lower half of the income distribution. This has blunted (but far from offset) the impact of the crisis.

The remarkably rapid and severe shocks imposed by COVID-19 illustrate the value of having in place channels to transfer income to vulnerable households. They enable policymakers to soften the effects of such rare disasters.

Looking forward

Great attention should now be devoted to developing a strategy for navigating the pandemic over the next 9-12 months. South Africa has begun a risk-based, alert-level approach to balance contagion risks and the economic consequences of lockdowns. Devising suitable responses will require that economists and epidemiologists work together to understand the mechanisms at work and balance the health dimensions of policies to contain the pandemic and the economic fallout – especially on vulnerable groups.

More generally, COVID-19 has highlighted vulnerabilities and made clear the urgent need to devise ways to make the economy more resilient to health, climate and other risks. One clear need is to rebuild fiscal space. Before the onset of the pandemic, national government debt was estimated to reach 65.6% of GDP in fiscal 2020/21. Lower revenues and higher demands for health spending and social assistance are adding pressure to already weak fiscal metrics.

Rekindling economic growth is key to creating this fiscal space. It is also key to building in other forms of resilience and to achieving development objectives. With a catastrophic global pandemic coming on top of more than a decade of disappointing economic growth, South Africa needs coordinated efforts to manage the pandemic over the next 9-12 months. It also needs a deliberate process to lay the foundations for sustainable, durable and inclusive economic development.